How Venice Was Built

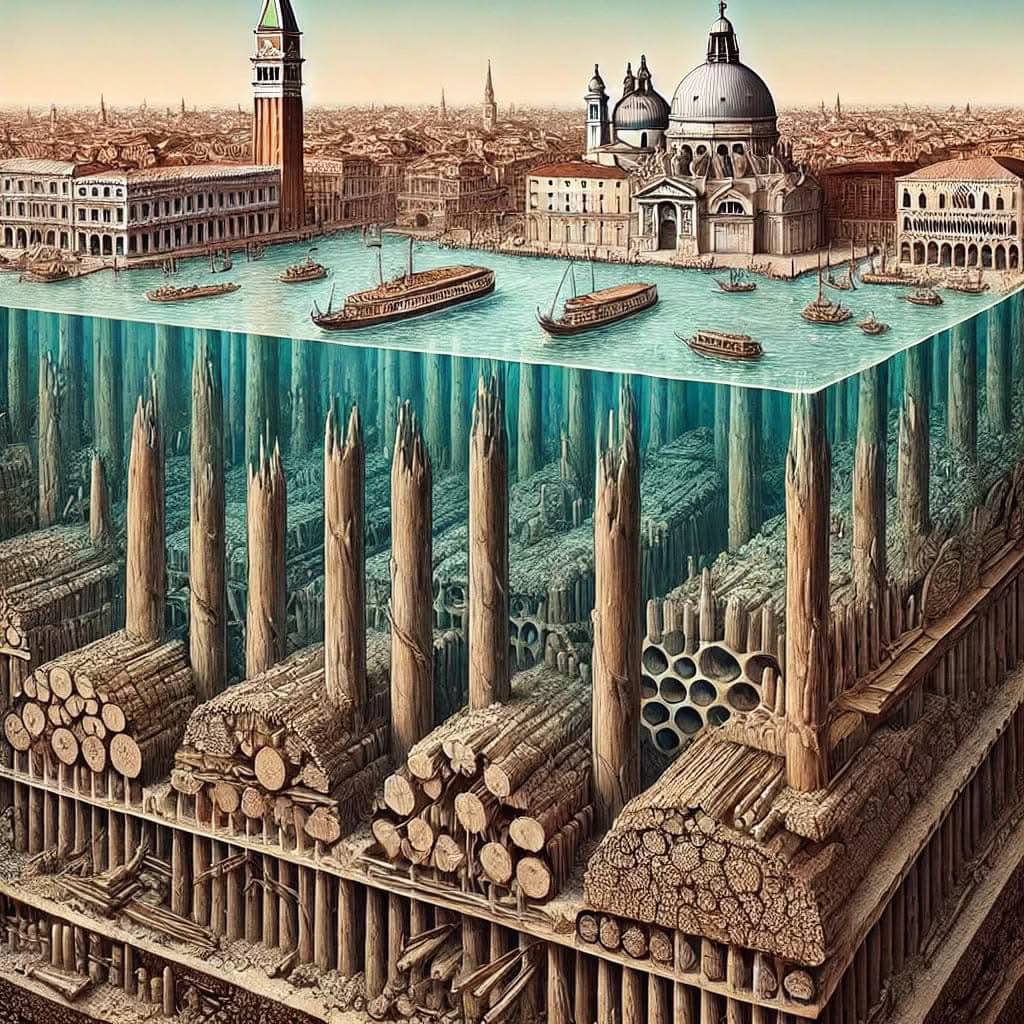

Venice: A City Floating on a Submerged Forest

Since 421 AD, Venice has stood on millions of tree trunks stuck into the clay bottom of the lagoon. Not steel or concrete, but mostly alder, with a few oaks, supporting the entire city.

In the salt water, these wooden pillars have petrified over time, becoming as hard as stone. St. Mark’s Campanile alone stands on 100,000 piles, while the majestic Basilica della Salute requires over a million trunks.

This unique structure extends up to three meters deep, with piles spaced just half a meter apart. At 1.6 meters below the waterline, this extraordinary feat of medieval engineering continues, after 1,500 years, to support one of the most fascinating cities in the world.

Venice’s reputation as a city “floating on a submerged forest” stems from its unique foundation, a marvel of medieval engineering adapted to the marshy lagoon environment. The city isn’t floating in the literal sense; rather, it’s built on a vast network of wooden piles driven into the lagoon’s muddy floor to create stable ground where none existed naturally.

Here’s how they did it:

- The Problem: Venice sits in a lagoon on the Adriatic Sea, surrounded by soft, shifting mud and silt rather than solid bedrock. Traditional stone foundations would sink under the weight of buildings in this waterlogged, unstable terrain.

- The Solution – Wooden Piles: Starting around the 5th century, Venetian builders used timber—mostly alder, oak, and larch from nearby forests—as the backbone of the city’s foundation. These trees were cut into long poles, typically 10–25 feet (3–8 meters) in length, and sharpened at one end. Workers drove millions of these piles vertically into the lagoon bed by hand, using sheer manpower and rudimentary tools. The piles were packed tightly together, often only inches apart, to form a dense grid.

- Why Wood in Water?: It seems counterintuitive to use wood in a wet environment, but the lagoon’s anaerobic (low-oxygen) mud played a key role. Without oxygen, the bacteria and fungi that cause wood to rot couldn’t thrive. Over centuries, the wood didn’t decay—instead, it mineralized, absorbing sediments and hardening into a stone-like consistency. This petrified “submerged forest” still supports Venice today.

- Building Up: On top of the piles, builders laid wooden platforms, then layers of waterproof clay and stone (often imported Istrian limestone). These acted as a base for brick and stone structures. The piles don’t reach bedrock—they’re not long enough—but the friction of the mud gripping the tightly packed wood provides surprising stability, distributing the weight of buildings across the network.

- Scale and Adaptation: Estimates suggest Venice rests on tens of millions of these piles. For example, the Santa Maria della Salute basilica alone reportedly sits on over a million. The system was so effective that it’s been replicated and maintained over centuries, with builders adapting to subsidence and rising sea levels by adding new layers or reinforcing foundations.

The result? A city that appears to defy nature, its palazzos and churches rising from the water atop a hidden wooden skeleton. It’s less a case of “floating” and more a triumph of anchoring.

Venice is pinned to the lagoon floor by this ancient, ingenious trick.