Why is the FDA funded in part by the companies it regulates?

By C. Michael White – Distinguished Professor and Head of the Department of Pharmacy Practice, University of Connecticut

The exterior of the Pfizer World headquarters building. Pfizer produced the first COVID-19 vaccine to gain emergency use authorization. Sam Aronov/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images

The Food and Drug Administration has moved from an entirely taxpayer-funded entity to one increasingly funded by user fees paid by manufacturers that are being regulated. Today, close to 45% of its budget comes from these user fees that companies pay when they apply for approval of a medical device or drug.

As a pharmacist and medication and dietary supplement safety researcher, I understand the vital role that the FDA plays in ensuring the safety of medications and medical devices.

But I, along with many others, now wonder: Was this move a clever win-win for the manufacturers and the public, or did it place patient safety second to corporate profitability? It is critical that the U.S. public understand the positive and negative ramifications so the nation can strike the right balance.

The FDA blocks thalidomide

Americans in the early 20th century were outraged when they found out that manufacturers used poor-quality methods for producing food and medication, and used unsafe, ineffective, and undisclosed addictive ingredients in medications. The resulting Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 gave the taxpayer-funded Food and Drug Administration new authority to protect the U.S. consumer.

One of the FDA’s most shining successes occurred in the late 1950s when the agency refused to approve thalidomide. By 1960, 46 countries allowed pregnant women to use thalidomide to treat morning sickness, but the FDA refused on the grounds that the studies were insufficient to demonstrate safety. Debilitating birth defects resulting from thalidomide arose in Europe and elsewhere in 1961. President John F. Kennedy heralded the FDA in 1962 for its stance. An FDA driven by the data – and not corporate pressure – prevented a major tragedy.

How AIDS changed how the FDA is funded

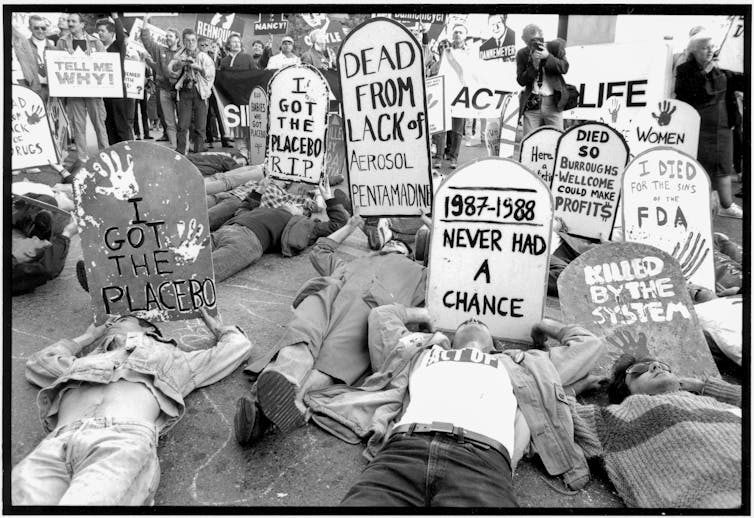

The FDA continued its work fully funded by U.S. taxpayers for many years until this model was upended by a new infectious disease. The first U.S. case of HIV-induced AIDS occurred in 1981. It was rapidly spreading, with devastating complications like blindness, dementia, severe respiratory diseases, and rare cancers. Well-known sports stars and celebrities died of AIDS-related complications. AIDS activists were incensed about long delays in getting experimental HIV drugs studied and approved by the FDA.

In 1992, in response to intense pressure, Congress passed the Prescription Drug User Fee Act. It was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush.

With the act, the FDA moved from a fully taxpayer-funded entity to one funded through tax dollars and new prescription drug user fees. Manufacturers pay these fees when submitting applications to the FDA for drug review and annual user fees based on the number of approved drugs they have on the market. However, it is a complex formula with waivers, refunds, and exemptions based on the category of drugs being approved and the total number of drugs in the manufacturers’ portfolio.

Over time, other user fees for generic, over-the-counter, biosimilar, animal, and animal generic drugs, as well as for medical devices, were created. As time passed, the FDA’s funding has increasingly come from the industries that it regulates. Of the FDA’s total US$5.9 billion budget, 45% comes from user fees, but 65% of the funding for human drug regulatory activities are derived from user fees. These user fee programs must be reauthorized every five years by Congress, and the current agreement remains in effect through September 2022.

Have user fees worked?

The FDA and the drug or device manufacturers negotiate the user fees. They also negotiate performance measures that the FDA has to meet to collect them and proposed changes in FDA processes. Performance measures include things such as how quickly the FDA responds to meeting requests, how quickly it generates correspondence, and how long it takes from submission of a new drug application until the FDA approves or refuses to approve a drug or product.

Because of the additional funding generated by user fees and performance measures that the FDA has to meet, the FDA is quicker and more willing to discuss what it wants to see in an application with manufacturers. It also offers clearer guidance for manufacturers. In 1987, it took 29 months from the time a new drug application was filed by the manufacturer for the FDA to decide whether to approve a medication in the U.S. In 2014, it only took 13 months and by 2018, it was down to 10 months.

Changes in more recent years have also increased the number of standard new drug applications approved the first time around by the FDA from 38% in 2005 to 61% in 2018. In diseases where there are not many medication options for patients, the FDA has a priority review process, where 89% of new drug applications were approved the first time around and the approvals were completed in eight months in 2018. All this occurred while the number of new drug applications have been increasing over time.

Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has seen the FDA provide emergency use authorization for potential treatments in a matter of weeks, not months. The infrastructure and capacity to review the available information so rapidly is due in large part to the funding from user fees.

While the number and speed of drug approvals have been increasing over time, so have the number of drugs that end up having serious safety issues coming to light after FDA approval. In one assessment, investigators looked at the number of newly approved medications that were subsequently removed from the market or had to include a new black box warning over 16 years from the year of approval. These black box warnings are the highest level of safety alert that the FDA can employ, warning users that a very serious adverse event could occur.

Before the user fee act was approved, 21% of medications were removed or had new black box warnings as compared to 27% afterward.

Some potential reasons that more adverse effects are coming to light after drug approval include senior FDA officials overturning scientist recommendations, a lower burden of proof for medication approval, and more clinical data in new drug applications coming from foreign clinical trial sites that require additional time to assess in an environment where regulators are rushing to meet tight deadlines.

Lack of money limits FDA

User fees are a viable way to shift some of the financial burden to manufacturers who stand to make money from the approval and sale of drugs in the lucrative U.S. market. Successes have occurred and provided U.S. citizens with medication more quickly than before.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

However, without careful consideration of what is being negotiated, the FDA can become weak and ineffective, unable to protect its citizens from the next thalidomide. There are some signs that the pendulum may be swinging too far in the direction of the manufacturers. Additionally, while drug approval functions at the FDA are well funded, the FDA is insufficiently funded to protect consumers from other issues such as counterfeit drugs and dietary supplements because they cannot collect user fees to do so. In my view, these functions need to be identified and require additional taxpayer funding.

Pingback: December 2021 Conservative Article Reference List | Fatherly Advice and Rants

Pingback: 2021 Conservative Article Reference List Archives | Fatherly Advice and Rants